Over the last few years I’ve had the pleasure of producing some episodes for ABC Radio National’s The Philosopher’s Zone. It’s a rare and precious thing that we have a dedicated philosophy outlet on the national broadcaster, and a real privilege to be able to produce programs for them!

Late in 2024 Deakin hosted the Australasian Society of Continental Philosophy conference, and my friend and colleague Cathy Legg organised a fascinating stream on the work of Wilfrid Sellars. Huge thanks to Cathy and to all the philosophers who agreed to share their insights on Sellars for the resulting program, “Rediscovering Wilfrid Sellars.”

New Radio Documentary: The Lost Boys of Daylesford

I’m very excited to say a documentary I’ve produced for Radio National, The Lost Boys of Daylesford, is available to download now!

On a clear, cold Sunday in June 1867, three little boys wandered away from their home near the town of Daylesford, on Dja Dja Wurrung country in central Victoria. Over the next six weeks the boys’ story gripped the colony, and made newspaper headlines around the world. Over a century later, the case continues to capture the imagination of locals and visitors to the region. Philosopher Patrick Stokes heads to Daylesford to find out why the lost children story has such enduring and haunting resonance.

This was a sad and haunting story to work on, but also a fascinating project that took me deep into volcano country to meet some really interesting people: Yvonne, who has tended the memorial on her own for nearly four decades, Megan who wrote a play trying to recover the mothers, and academics piecing together how lost children became such a distinctive and persistent part of the Australian cultural imaginary.

This was also the first non-comedy project Christian Price and I have collaborated on in over 26 years of working together!

I hope you enjoy it, and if you do, please spread the word.

DIGITAL SOULS: A Philosophy of Online Death

Social media is full of dead people. Untold millions of dead users haunt the online world where we increasingly live our lives. What do we do with all these digital souls? Can we simply delete them, or do they have a right to persist? Philosophers have been almost entirely silent on the topic, despite their perennial focus on death as a unique dimension of human existence. Until now.

Drawing on ongoing philosophical debates, Digital Souls claims that the digital dead are objects that should be treated with loving regard and that we have a moral duty towards. Modern technology helps them to persist in various ways, while also making them vulnerable to new forms of exploitation and abuse. This provocative book explores a range of questions about the nature of death, identity, grief, the moral status of digital remains and the threat posed by AI-driven avatars of dead people. In the digital era, it seems we must all re-learn how to live with the dead.

“Eloquently written, choc-a-bloc with piquant stories of tech history, and combined with the penetrating philosophical analysis we have come to associate with the author, Digital Souls is a rigorous and yet accessible mediation on the perennial question of personal identity as it intersects with our evolving cyber self-personifications. It is a rare feat, but there is enough history of philosophy in these pages to satisfy scholars without losing non-academic readers. In sum, the smart move would be to put away your Smartphones for an hour or three to digest this wise and entertaining reflection on how new-technologies of the self are molding our understanding of personal immortality and alas, what it means to be a self.” – Gordon Marino, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy, St. Olaf College, USA

“Digital Souls is a little gem of applied philosophy, and Stokes’ erudition is undiminished by the lightness and accessibility with which he presents it. Scholars and general readers alike will have their assumptions constructively disrupted by this book, and it’s certainly been a long time since I was this enjoyably provoked.” – Elaine Kasket, author of “All the Ghosts in the Machine”

“Online technologies have allowed us to extend ourselves ever further in space, time and memory. But have they thereby allowed us to ‘cheat death’? Digital Souls is a seminal investigation of this possibility and the ethical quandaries it raises for all who live in a digitalized social world.” – Michael Cholbi, Professor of Philosophy, University of Edinburgh, UK

“This is a fascinating exploration of how online sites and resources represent, and, in some ways, transform death. The book is written in a lively and accessible style. It helps us to understand our attitudes toward death in a new and illuminating way. Highly recommended!” – John Martin Fischer, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, University of California, Riverside, USA

New radio program: “Gloomy Sunday”

Suicide is one of the oldest philosophical problems – yet it’s also an inherently risky thing to talk about. So what happens when philosophers today go to talk to the public about suicide?

Glad you asked, because as it happens I’ve produced an episode of ABC Radio National’s “The Philosophers Zone” on this very topic. ‘Gloomy Sunday’ features Deakin’s Dr Jon Roffe and Dr Valery Vinogradovs alongside the University of Melbourne’s A/Prof Justin Clemens and Prof. Jane Pirkis.

You can listen to the program here, or wherever you get your podcasts.

New Documentary: Last Light

There’s a story I was a bit obsessed with as a child. I was that weird, nerdy kid that was massively into UFOs, ghosts, the paranormal etc. I read everything I could find and bored anyone who was within earshot. But this one story in particular stood out.

There’s a story I was a bit obsessed with as a child. I was that weird, nerdy kid that was massively into UFOs, ghosts, the paranormal etc. I read everything I could find and bored anyone who was within earshot. But this one story in particular stood out.

It happened in my home city, in the year I was born. And it took a life.

I still remember riding my bike (black BMX with white tyres; the kids called me Nutty Professor White Wheels, which tells you a lot about me at that age) down to Moorabbin City Library in Bentleigh after school to photocopy news clippings about the case. I even wrote to the local UFO group, VUFORS.

Somewhere during my teens, something shifted. I went from believer to skeptic, but the kind of skeptic who’s less interested in debunking and more interested in what these extraordinary human experiences say about us.

But that one story. That story never left.

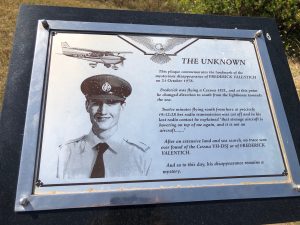

People at this latitude still know the name of Frederick Valentich, or if they don’t, they recall there was a young pilot who vanished over Bass Strait. A family’s tragedy had morphed into an eerie piece of modern Australian folklore – except, of course, it wasn’t just folklore. A man was missing, presumed dead.

The story always finds its way back again: anniversaries, new bits of detail, TV shows with recreations of the final flight and the aftermath. Books. Podcasts. It seeped into our culture. Henri Szeps did a one-man play based on it. The Kettering Incident drew on it.

The story and I both turned 40 last year. I found myself thinking about it more and more, reading the newly discovered Department of Transport investigation file, unsettled to find I was now less sure of what “really” happened than ever.

What was striking now was how the central figure in the story was constantly being overwritten by other people’s interpretations of what happened to him. With every telling, a totally different Frederick.

I wanted to trace all those different Freds back to their source. And I wanted to know what happened to the people left waiting for that plane to come back. What it’s like to live for four decades suspended in that kind of uncertainty.

And that’s how I found myself at Moorabbin Airport with a bunch of recording gear, exactly forty years to the day since the disappearance.

This project has been pretty all-consuming for nearly a year now, and I don’t think the story is finished with me yet. I’m a bit terrified how this piece will be received. It’s almost certainly going to be misinterpreted in some quarters.

This project has been pretty all-consuming for nearly a year now, and I don’t think the story is finished with me yet. I’m a bit terrified how this piece will be received. It’s almost certainly going to be misinterpreted in some quarters.

But it’s here. I want to thank supervising producer Lyn Gallacher – herself a pilot – for her wisdom and guidance, Michelle Rayner for taking a chance on me, Jack Montgomery-Parkes for his impeccable ear and unerring timing, Irene and everyone VUFORS for trusting me to come into their space, and George, Mike, and Chris for sharing their recollections.

Above all, I want to thank Rhonda and Steve for being willing to speak to me about the evening in 1978 that they are both, in their very different ways, still anchored to.

So, here it is. Here’s Last Light.

Last Light: The Valentich Mystery premieres on ABC Radio National’s The History Listen, Tuesday 4th June 2019 at 11am, repeated Saturday 8th June 5:30pm and available for download anytime.

Teaching Ethics: What’s the Harm?

In their (not infrequent) darker moments, academics have been known to observe wryly that students’ grandparents seem to die at a much higher frequency near exams, requiring the students to have time off for the funeral. The ‘Dead Grandmother Problem’ has even been the subject of (tongue-in-cheek) academic research demonstrating that based on extension requests, the period before assessments are due is a very dangerous time for students’ relatives. This is, of course, rather unfair: students may lie to their lecturers sometimes, but people do die, and they rarely time their deaths to accommodate their relatives’ exam schedules. Moreover, as the blogger Acclimatrix has pointed out, the ‘dead grandparent’ might actually be a polite euphemism for something traumatic the student cannot (or in any case shouldn’t be expected to) disclose to their teachers. In any event, anyone who has taught a large college or university class quickly comes to realise there is a huge amount of illness, sadness, violence, disability, and loss in the background of what we see in the classroom. We only ever get glimpses of what goes on in our students’ lives, and those glimpses are often quite distressing. Imagine all the things we don’t see.

Read the rest of this article at Philosophy Now

Free Speech or Public Harm?

One thing you have to give Steve Bannon: he knows how to get people yelling at each other. The former Trump chief strategist and Breitbart editor may be greatly reduced on paper, but he continues to exert a disturbing influence on global affairs – and start fights just by turning up, and sometimes not even that.

Just in the last couple of weeks, he managed to cause upset simply by accepting invitations: in Australia, giving a one-on-one interview on the ABC’s ‘Four Corners’ program, and in the US by being invited and then disinvited to an on-stage session at the ‘New Yorker’ magazine’s ideas festival, after several other speakers pulled out in protest.

These events feed into a larger, ongoing contested narrative about free speech and harm. On the one hand, there’s a liberal charge that the “censorious” left is silencing right-of-centre voices via “no-platforming,” and thereby repressing speech rights and stifling debate. On the other, there’s the view that inviting those whose views serve and entrench various forms of oppression to speak in public fora causes real harm to the marginalised, by treating those views, even if only implicitly, as somehow worth discussing.

Read the rest of this article at Deakin’s Invenio

John Clarke: an unsurpassed craftsman of the Australasian voice

There are some writers whose voice, by sheer accident of timing in your life, reach far deeper into your brain than the specifics of what they wrote.

For me, it was the satirist and actor John Clarke, who died suddenly on Sunday while hiking in the Grampians, aged 68. I never met Clarke. But he taught me a great deal about the English language and the Australasian voice, and what can be done with both.

Clarke was a transplanted New Zealander who became an essential Australian presence. As a young man he’d swapped the shearing shed for university without ever losing his clear affection for both worlds. That sums up the sense of duality in Clarke’s persona, firmly at home yet ever so slightly removed from the absurdity around him.

The ideal posture for the satirist, in other words. And his facility with language was wholly unrivalled in Australian satire.

One of my earliest comedy memories was my parents’ copy of The Fred Dagg Tapes. I had no idea who Whitlam or Kerr were, but I hung on every word. You have to. You cannot listen to Clarke even at his most seemingly flippant without sensing the incredible precision of the word choices and the careful elegance with which his sentences are shaped and finessed. Every flourish and detour, every wry circumlocution, is perfectly formed and placed.

In that craftsmanship lies the unnerving durability of Clarke’s work. So much of early 1980s Australia seems impossibly alien now, yet Fred Dagg’s musings on real estate could have been written yesterday:

You can’t write like that anymore. The media that services our Twitter-addled attention spans won’t reward phrases like “probably isn’t going to glisten with rectitude” or “why you would want to depart too radically from the constraints laid down for us by the conventional calibration of distance?,” or writing insider send-ups of literature (“the stark hostility of the land itself – I’m sorry, the stark hostility of the very land itself”) or entire books parodying major poets with perfect pitch.

Clarke could invite his reader into jokes about Samuel Richardson (“he’s probably dead now, he was a very old man when I knew him”) or Ibsen and Monet playing tennis

without a trace of pretension or smugness. His Commonplace pieces for Meanjin reveal a remarkable racconteur with an obvious curiosity for people and places. Above all, his work is shot through with an unflagging affection for language itself. And, in deference to the fact this is supposed to be a philosophy column, we should note his unique take on Socratic Paradox:

To call what Clarke did sarcasm seems at once too crude and too weak. It’s a dryness beyond sarcasm. To work at all, irony has to find a way to signal the speaker’s ironic distance from what they’re saying. The question is how you do it. Sarcasm screams it at you; subtler irony gives you a knowing wink. Clarke doesn’t have to wink. It’s there already, something at the top of the throat, in the posture, in something the forehead’s doing. A near-total irony perfect for dissecting the deadly serious.

Clarke’s was a voice that was Australasian in the best sense: refusing self-importance but finding a deep earnestness in taking the piss.

He didn’t do impressions or voices, he just did his voice. It didn’t matter who he was meant to be: the voice sounded right. It sounded right as any politician you care to mention, it sounded right as Wal Footrot, and it sounded right as the conniving developer in Crackerjack.

It was a finely-tuned instrument in The Games. In a country that lurches alarmingly between cultural cringe and shallow triumphalism, The Games hit the sweet spot in the national neuroses in a way that’s unlikely ever to be repeated.

And it was never better than when he and Bryan Dawe deftly unweaved the tortured logic of the week with paradoxically brutal restraint. Clarke and Dawe was a masterpiece precisely because two middle-aged men in unremarkable suits against a black background, not even attempting an impression or costume, made a space where the latest absurdity could be made to disassemble itself in front of us.

Urgency in wryness. Bemused ferocity. We so dearly need voices like that, but we’ve just lost the best we had.

![]() Vale Mr Clarke. We’ll not see your like again.

Vale Mr Clarke. We’ll not see your like again.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The Vice President Dines: A Philosophical Dialogue

[In a swanky Washington DC restaurant, L’Metaphysique, VICE PRESIDENT MIKE PENCE is enjoying an intimate dinner with his wife and constant companion KAREN PENCE]

MIKE PENCE So I said, “Well, Don, if they’ve got the video, and it’s really that bad, why don’t you just” – Karen? Karen, what’s wrong? Is the steak a la potus ok?

KAREN PENCE Sorry, Mike, I just feel a bit… funny…

[KAREN PENCE begins to vibrate alarmingly, and an earthly blinding light suddenly engulfs the room along with a loud humming noise. The light subsides to reveal TWO KAREN PENCES sitting next to each other. They are exactly similar in every way: same body, same clothes, same everything]

MIKE PENCE What the hell?? Karen? Karen what’s going on?

[Pandemonium has broken out. The Secret Service are frantically trying to work out what’s going on, while waiters and diners run around madly. Amid the confusion, an English man with a wild crop of white hair approaches the table. Among this man’s more striking features is that he is quite transparent.]

PARFIT Forgive the intrusion, Mr Vice President, but I believe I might be able to shed some light on this. I’m the late Derek Parfit.

MIKE PENCE Sorry, did you say Parfit? The highly influential Oxford philosopher who died recently? The most important philosopher of personal identity since Locke?

PARFIT How jarringly improbable that you knew that.

Anna Riedl/Wikimedia Commons

MIKE PENCE Never mind the background, man, tell me what the hell is going on here!

PARFIT Oh it’s perfectly straightforward, really. Your wife has fissioned. Split in two like an amoeba, into two qualitiatively identical individuals. Each individual is both physically and psychologically continuous with your wife as she was before the fission event. So each individual remembers everything your wife remembered up until the moment she split in two. Call this scenario The Second Lady.

MIKE PENCE Why… why are we giving this situation a title?

PARFIT Sorry, force of habit. I’m afraid this does raise rather an awkward question for you, though. I understand there’s been quite a lot of attention paid recently to your policy of not dining alone with a woman other than your wife?

MIKE PENCE Well of course I don’t. The Billy Graham Rule makes perfect moral sense. I mean, what possible legitimate reason could a man have for dining alone with a woman he’s not married to?

PARFIT So, shall we ask the waiter to move you to another table then? I’m sure you wouldn’t like to continue to sit with these women without your wife present.

MIKE PENCE What do you mean, ‘without my wife present’? She’s right here! Aren’t you honey?

KAREN PENCE 1 AND KAREN PENCE 2 [in unison] Yes Mike, I’m here.

[They both turn and glare at each other]

PARFIT You see the difficulty, Mr Vice President. Both women are psychologically connected to your pre-fission wife in the same way as your wife would have been had she not fissioned. Each has the memories, committments, and character of Karen Pence.

MIKE PENCE Ok, so they’re both my wife then!

PARFIT They’re both your wife? Why, that’s bigamy!

[A WAITER turns around]

WAITER Yes, and it’s bigamy too. It’s big of all of us. Let’s be big for a change!

MIKE PENCE You’re accusing me, a deeply conservative Christian who won’t even attend an event where alcohol is served if his wife isn’t present, of bigamy?

PARFIT Well, you’re claiming that each of these women is your wife.

MIKE PENCE No, I’m saying, they’re… they’re both my wife. My one wife, Karen.

PARFIT I’m afraid that’s impossible. They’re clearly two separate individuals. They may be exactly alike – though in time of course they’ll diverge psychologically – but if they’re sitting next to each other rather than occupying the same space then by Leibniz’s Law they can’t be the same person.

[MIKE PENCE looks aghast]

MIKE PENCE You mean one of them’s my wife and one’s an impostor? So which one’s really my wife then?

PARFIT Ah, I’m afraid that solution won’t work either, Sir. After all, they’re qualitatively, but not numerically, identical. Each has just as good a claim to be Karen Pence as the other.

BOTH KAREN PENCES But I’m Karen Pence!

PARFIT Well you can’t both be Karen Pence, but there’s also no non-arbitrary grounds on which we could declare one of you to be Karen Pence but not the other. Fission doesn’t preserve identity. Thus, neither of you are Karen Pence. And you, Mr Vice President, are now having dinner alone with two women who aren’t your wife.

MIKE PENCE You mean I… I have to move tables?

BOTH KAREN PENCES Is that really your biggest concern right now?

MIKE PENCE Sorry, rules are rules… [suddenly very formal] ladies.

U.S. Army Sgt. Kalie Jones/Wikimedia Commons

PARFIT Well, before we all get too despondent, look at what The Second Lady teaches us: neither of these women is strictly identical with Karen Pence. Thus, Karen Pence has not survived. And yet, it seems completely wrong to say Karen Pence has died; if anything, apart from some initial awkwardness, this situation may even be much better than ordinary survival. The Second Lady preserves everything we care about in ordinary survival, and adds more of it. There is still someone to carry out the duties of Second Lady of the United States – indeed, there are now two people to do so, and the duties of office will correspondingly be less onerous. Karen Pence had both official duties and a passion for art therapy; now both can be pursued to twice the extent as before. From this we may conclude that identity is not what matters in survival.

MIKE PENCE Do you always talk like this?

PARFIT I did. On paper, anyway.

BOTH KAREN PENCES So where does this leave us?

MIKE PENCE I’m so confused.

[The restaurant doors swing open and PRESIDENT TRUMP walks in]

DONALD TRUMP Pence! Great to see you. Hey, how about I join you? Let’s get some more steaks over here! Extra well done! Just the best steaks. So beautiful, you’re gonna love these steaks.

![]() ALL THREE PENCES Check, please.

ALL THREE PENCES Check, please.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

POSTSCRIPT: After I’d published this on The Conversation, two interesting things happened. The first is that a couple of people rightly pointed out that Mike Pence probably wouldn’t say ‘hell’ so much. That’s fair, and in hindsight it clearly detracts from the otherwise perfect realism of the piece…

Secondly, on Facebook, my colleague from Herts, Brendan Larvor, replied that if identity doesn’t survive fission, there is in fact no problem here: as Karen Pence does not exist post-fission, the Vice-President is now single, and thus is free to dine with whoever he pleases.

Senator, You’re No Socrates

So, we all knew Malcolm Roberts, former project leader of the climate denialist Galileo Movement turned One Nation politician, would make an ‘interesting’ first speech to the Senate. If you’ve been following Senator Roberts’ career, most of what he said was more or less predictable. The UN (“unelected swill” – take a bow, PJK), the IMF and the EU are monstrous socialist behemoths with a “frightening agenda,” climate change is a “scam,” the “tight-knit international banking sector” (a dangerous phrase given Roberts’ history of discussing international “banking families”) are “One of the greatest threats to our liberty and life as we know it.”

It may be startling to hear this in one concentrated burst, from a senator, last thing on a Tuesday afternoon, but if you’re familiar with the more conspiratorial corners of the internet this was all fairly pedestrian stuff.

What was more surprising, at least in passing, was Roberts comparing himself to Socrates:

Like Socrates, I love asking questions to get to the truth.

A Socratic questioner in the Senate! The gadfly of Athens, who cheerfully punctured the delusions of the comfortable and reduced them to frozen bewilderment with just a few cheerfully framed questions like some Attic Columbo, has apparently taken up residence in the red chamber. This should be a golden age for rational inquiry, right?

Right?

Epistemic revolt

The choice of Socrates, like that of Galileo, is no accident. Both fit neatly into a heroic “one brave man against the Establishment” narrative of scientific progress that climate denialists like to identify with. Both eventually changed the trajectory of human knowledge. But along the way, both suffered persecution. Galileo was made to recant his “heretical” heliocentrism under threat of torture and spent his last years under house arrest. Socrates, charged with impiety and corrupting the youth and denounced in court by one Meletus, was put to death. Of course that’s not nearly as rough as the brutal suppression of Malcolm Roberts, who has been cruelly oppressed with a three year Senate seat and a guest slot on Q&A. But you get the idea.

We've had a pause in warming & NASA corrupted data, says Malcolm Roberts. @ProfBrianCox examines the graphs #QandA https://t.co/HTNk4Bzrk1

— ABC Q&A (@QandA) August 15, 2016

Most importantly, both Socrates and Galileo function here as emblems of a kind of epistemic individualism. They’re ciphers for a view of knowledge generation as a contest between self-sufficient individual thinkers and a faceless, mediocre ‘they,’ instead of a collective and social process governed by internal disciplinary norms and standards.

Roberts doesn’t simply like asking questions – anyone can do that. No, he wants to be like Socrates: someone who refuses to accept the answers he’s given, and dismantles them with clinical, exhaustive precision. Malcolm Roberts wants to work it all out for himself, scientific community be damned. If Socrates could, why can’t he? Why can’t each of us?

Distributed knowledge

But Socrates, living at the dawn of scholarly inquiry, had the luxury of being a polymath. “Philosopher” simply means “lover of wisdom,” and early philosophers were forced to be rather promiscuous with that love. Physicist, logician, meteorologist, astronomer, chemist, ethicist, political scientist, drama critic: the Greek philosopher was all of these and more by default. The intellectual division of labour had not yet taken place, because all fields of inquiry were in their infancy.

Fast forward two and a half thousand years and the situation is radically different. The sciences have long since specialised past the point where non-specialists can credibly critique scientific claims. There is now simply too much knowledge, at too great a pitch of complexity, for anyone to encompass and evaluate it all. The price we pay for our expanding depth of knowledge is that what we know is increasingly distrubuted between the increasingly specialised nodes of increasingly complex informational networks.

That fact, in turn, emphasises our mutual epistemic dependence. I rely daily on the expert competence and good will of thousands of people I never see and will never meet, from doctors to builders to engineers and lawyers – and climate scientists, who wrangle with the unimaginably complex fluid dynamics of our planet.

So what do you if you find yourself up against a network of specialist knowledge that disagrees with your core beliefs? Do you simply accept that you’re not in a position to assess their claims and rely, as we all must, on others? Do you, acknowledging your limitations, defer to the experts?

If you’re Socrates today, then yes, you probably do. The true genius of Socrates as Plato presents him that he understands his limitations better than anyone around him:

And is not this the most reprehensible form of ignorance, that of thinking one knows what one does not know? Perhaps, gentlemen, in this matter also I differ from other men in this way, and if I were to say that I am wiser in anything, it would be in this, that not knowing very much about the other world, I do not think I know. (Apology 29b)

Dismissing expertise

But deferring to those who know better is not the sort of Socrates Malcolm Roberts wants to be. If you want to be a Roberts-style Socrates, instead of conceding your ignorance, you cling to some foundational bit of putative knowledge that allows you to dismiss anything else that’s said, like so:

It is basic. The sun warms the earth’s surface. The surface, by contact, warms the moving, circulating atmosphere. That means the atmosphere cools the surface. How then can the atmosphere warm it? It cannot. That is why their computer models are wrong.

This is a familiar move to anyone who’s ever watched a 9/11 truther at work. While “jet fuel can’t melt steel beams!” has become a punchline, in some ways it’s the perfect battle-cry for epistemic rebellion. It asserts that if you just cling to some basic fact or model, you can use it to reject more complicated scenarios or models that seem to contradict that fact.

That move levels the playing field and hands power back to the disputant. Your advanced study of engineering or climatology, be it ever so impressive, can’t override my high school physics or chemistry. My understanding of how physical reality works is simple, graspable, and therefore true; yours is complex, counterintuitive, esoteric, and thus utterly suspect. I’m Plato’s Socrates: earthy, self-sufficient and impervious to sophistry; you, by contrast, are Aristophanes’ Socrates, vain and unworldly, suspended in your balloon far above the healthy common sense of the demos, investing the clouds with your obsessions.

Auxiliary Accusations

This leaves our would-be Socrates with the awkward fact that all those experts still disagree with him. How do you respond in the face of such disconfirmatory data? You could abandon your hypothesis, or you could deploy what Imre Lakatos called an ‘auxiliary hypothesis’ to defend it.

In Roberts’ case, as with many conspiracy theorists, this auxiliary hypothesis takes the form of a scattergun accusation. Climate science isn’t just mistaken, or even just inept, but “fraudulent.” Roberts is quite prepared to accuse thousands of people whose lives he knows nothing about of conscious and systemic corruption rather than admit he might be wrong.

From within Roberts’ rather Manichean worldview, that might seem to make a certain kind of sense: the forces of freedom are fighting an apocalyptic battle against the forces of repression. The enemy is positively evil, with its cooked climate data and insidious agendas and overtaxed bread. There is no need to spare the feelings of a foe so wicked. Those greedy bastards knew exactly what they were doing when they signed up for Socialist Climate Data Manipulation Studies in O-Week.

![]() For anyone who claims to care about the quest for knowledge like Socrates did, the moral recklessness of such an accusation, from someone in such a position of power, should be cause for alarm. And when you’re trying to destroy the reputation of researchers because their message doesn’t suit your free-market pieties, you might just be more Meletus than Socrates.

For anyone who claims to care about the quest for knowledge like Socrates did, the moral recklessness of such an accusation, from someone in such a position of power, should be cause for alarm. And when you’re trying to destroy the reputation of researchers because their message doesn’t suit your free-market pieties, you might just be more Meletus than Socrates.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.